First the bad –or possibly good – news. Your online purchase will not be beamed into your home, and nor will B2B shipments. Goods will continue to be moved by various modes of transportation. Air cargo will still pass through warehouses on more or less congested airfields and continue to spend more time on the ground than in the air.

Depending on how far away tomorrow is, though, there will be differences in the detail. In some cases there might not even be a shipment, or inventory.

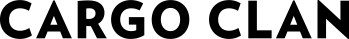

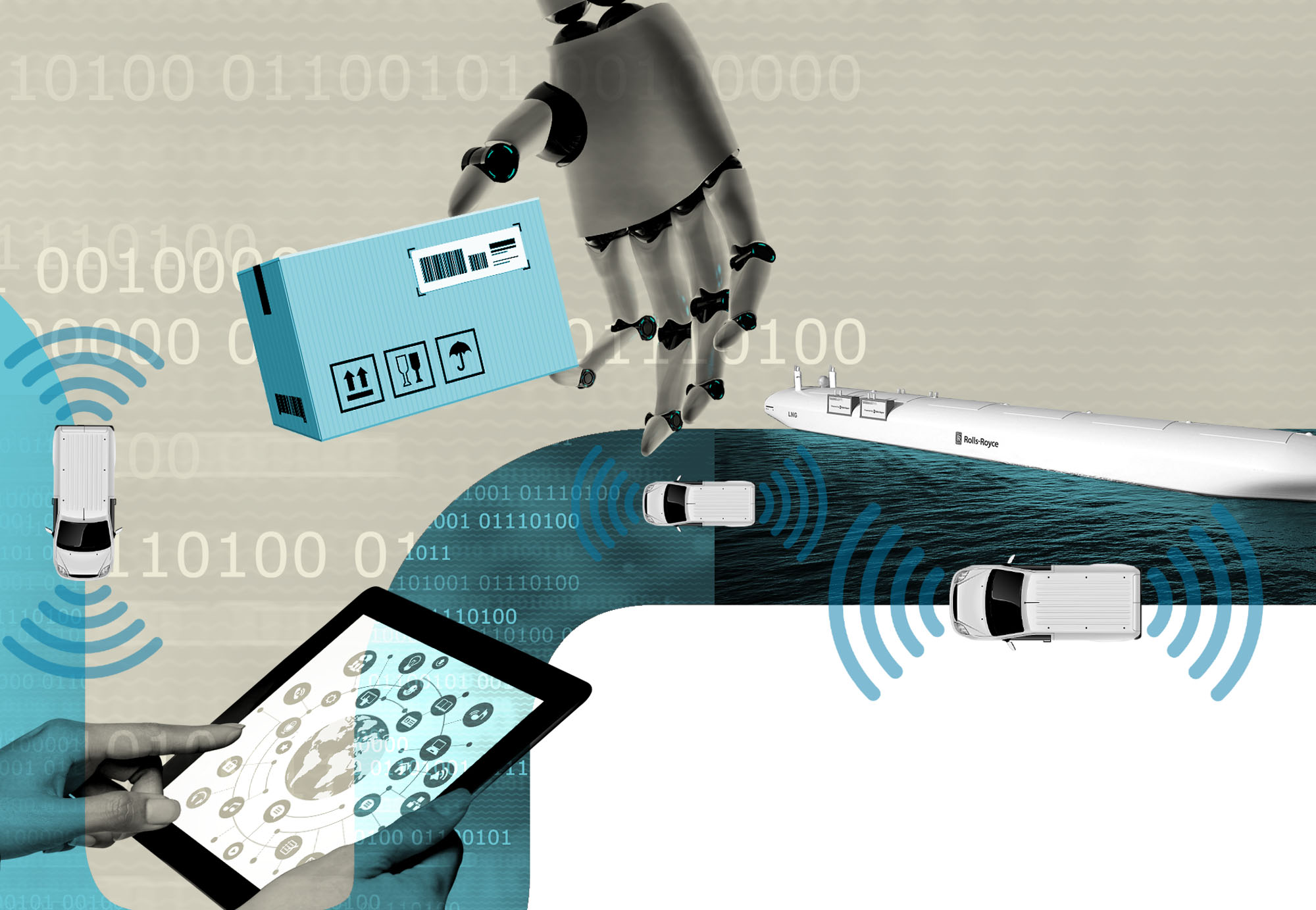

The line-up of vehicles that move goods is set to expand, and will include self-driving units on the ground as well as unmanned aerial devices. The 2016 version of DHL’s forward-looking Logistics Trend Radar notes that while self-driving vehicles and drones are already on the scene, they are still some time away from assuming a defined role in logistics.

Marcel Fujike, senior vice-president for products and services, global air logistics at Kuehne + Nagel, predicts that drones will really come to the fore in rural areas rather than densely populated centres. ‘We already see some moves in Africa,’ he says.

Ram Menen, former head of cargo at Emirates and ex-chairman of TIACA, thinks it will be a while before the skies are blackened with delivery drones. ‘Drones can carry small parcels, but I don’t think we will see large numbers taking to the air for a while yet,’ he says.

Regulators too would baulk at the idea of thousands of these devices flying around, but Menen adds that in the longer term a regulatory framework and operating corridors will be created for them.

This will also be the case for the deployment of larger drones capable of carrying payloads of two or three tonnes, he reckons. ‘Most likely these will operate on set routes between facilitation centres,’ he says.

By the same token, remotely controlled unmanned freighter aircraft will not make an entry before regulators are satisfied that clear operating parameters are in place. Anselm Eggert, vice-president of strategy and business development at Lufthansa Cargo, thinks that cargo planes will take the lead there ahead of passenger aircraft but acknowledges that no plans for such aircraft exist.

‘In the next five years there will not be huge change,’ he says. ‘There will be developments and projects. The really big changes will kick off in five years, but we will really get there in 10 years.’

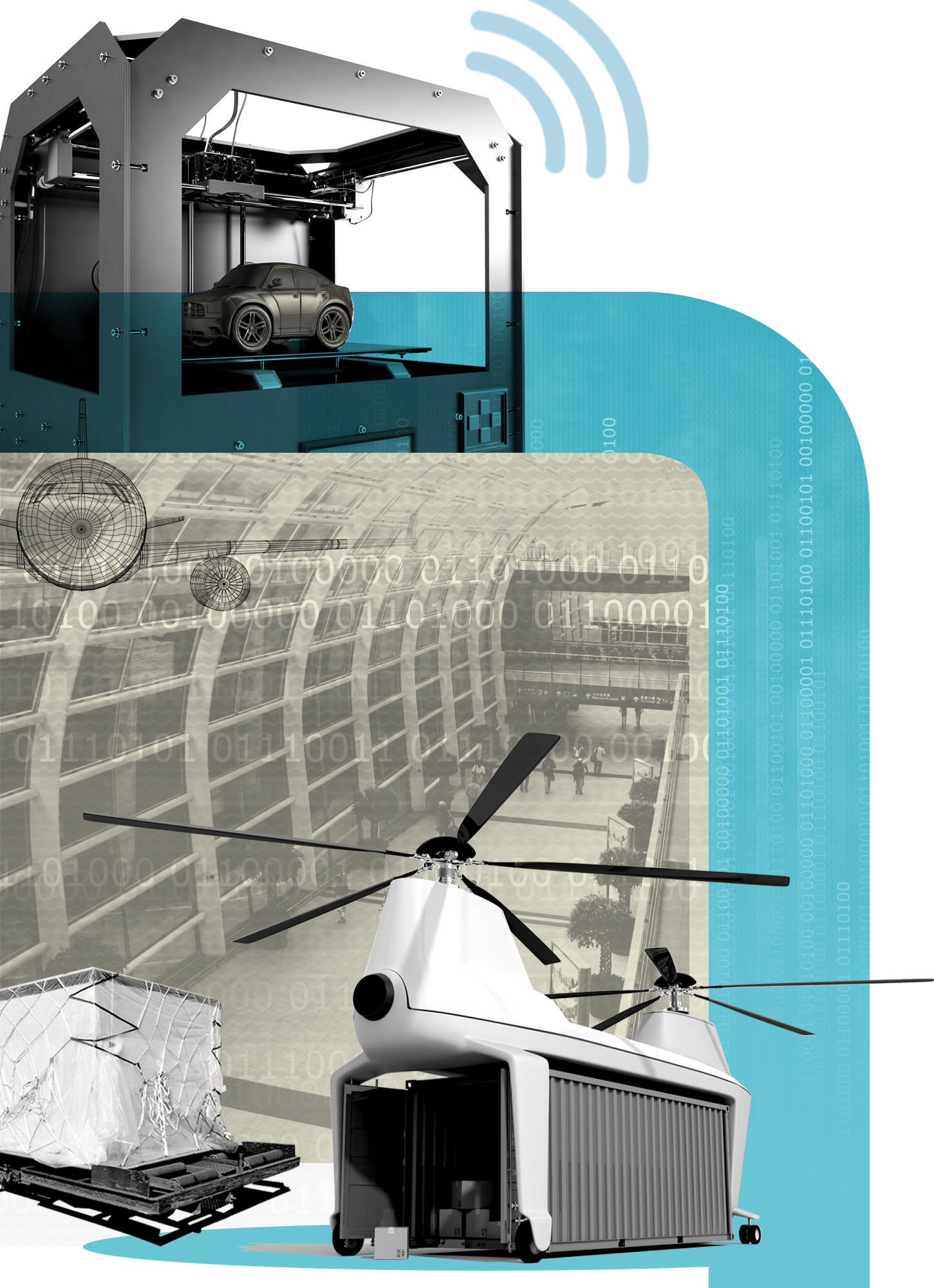

This tallies with DHL’s Logistics Trend Radar, which envisages the establishment of big data, cloud logistics, augmented reality and anticipatory logistics within the next five years. Its authors see high-profile game changers such as 3D printing, self-learning systems, unmanned aerial vehicles and self-driving vehicles still more than five years away.

HOT AIR

However, Menen is positive that another type of transportation vehicle will be in operation much earlier. He sees airships coming into play in two or three years, pushing their way into the project market.

‘Today, generators are based on the size of the pieces that can be transported to where they are assembled, but what if a factory were able to produce a generator three times the size of what we see today, which gets lifted by an airship and placed on the site?’ he asks.

While new aerial vehicles might be stewing in the slow lane to market, overtaken by slower moving airships, the flow of data looks set to accelerate hugely. Additionally, the sheer volume of available data will engender new analytics, and in turn new services, according to many pundits.

In line with Logistics Trend Radar, many expect big data to be the segment to take off soonest and to have the greatest impact in the near term.

‘The biggest change will be in automation and transparency,’ predicts Zvi Schreiber, CEO of logistics technology developer Freightos. He sees vast room for automation in the air-cargo sector. ‘This industry has a lot of data, and they’ve all been offline,’ he says.

Lufthansa Cargo’s Eggert regards the Internet of Things (IoT) as a powerful driver of the push to digitising the industry, which will lead to enhanced performance levels and new services. ‘We want to connect the Internet of Things with air- cargo systems,’ he says.

The authors of the Logistics Trend Radar project that by 2020, more than 50 billion objects will be connected to the internet, presenting huge opportunities for the logistics sector.

The availability of data – possibly stored in data clouds for access from all parties involved in a shipment – will not only give operators more detailed insights, but should also help them with forward-looking measures. ‘We need to start to look into the future and start to use predictive analytics,’ says Fujike.

GUESSING GAME

One of the up and coming developments in Logistics Trend Radar in the near future is the evolution of anticipatory logistics. The authors envisage early moves of goods to distribution centres in anticipation of sales, based on customer data analysis. Other likely scenarios are predictive maintenance and predictive supply-chain risk-management.

The sheer volume of data and the complexity of the algorithms employed for such undertakings will rely heavily on computing power. This is where artificial intelligence (AI) can come into play, such as systems with the learning power to discern patterns in data that can lead to the development of specific solutions for individual customers or groups of them.

‘Tomorrow’s world is going to be driven by analytics,’ predicts Menen. ‘AI does the back end and puts together data that highlight certain points for humans to work on. The humans don’t deal with background analytics.’

Like driverless vehicles and 3D printing, Schreiber sees this further in the future. At this point data are not standardised and consistent enough for AI to work, he remarks.

SHARE AND SHARE ALIKE

Based on the greater volume and availability of data, a new class of logistics firms, one rung up from 4PLs (supply chain integrators), could arise to manage ‘supergrid logistics’. Their primary focus would be the ‘orchestration of global supply-chain networks that integrate swarms of different production enterprises and logistics providers’, according to the Logistics Trend Radar.

Such scenarios hinge on flow of data between different parties – but transparently. Beyond the necessary digitisation, this is contingent upon a much greater degree of collaboration and openness. ‘You need data sharing – not only between airline and forwarder but also between forwarders,’ says Freightos’ Schreiber.

Menen feels that the air cargo industry has some catching up to do. ‘Collaboration is the way forward, but it’s not going to happen with the current mindset. Ocean carriers and truckers are more evolved there,’ he says.

To get there could require a change of the business model. ‘Everybody is trying to make a buck off each other,’ he says. ‘That’s got to stop. We need win-win situations that allow the joint development of better solutions for the customer.’

Most likely, change will be forced upon the industry from outside. Menen says that the future of the industry will not be driven by the large multinational forwarders but by the likes of Google and Amazon.

Fujike, though, is not worried by their impact on logistics and dismisses predictions of the demise of the middleman, which he finds reminiscent of doomsday scenarios for forwarders bandied about when the integrators were on the rise 25 years ago.

‘So far these are facilitators,’ he says. ‘They bring parties together, but what happens if a shipment gets stuck? Their solution is only as good as their suppliers’ solution.’

Menen thinks that the manufacturing side could have a more profound impact on logistics once 3D printing takes off. ‘3D will do the same to the industry as the internet did to the print media,’ he says. He recalls the demise of the bundles of newspapers flown to readers around the world, which can now be printed instantaneously in multiple locations. By the same token, consumers might be able to download a design for an object like a mug and print it at home, instead of buying a mug made in the US in a store in Kuala Lumpur. Duties and transportation costs disappear in this scenario.

If there is to be a casualty, Menen thinks that the marine industry will suffer the most, as companies will not keep inventory.

Eggert is less concerned. Instead of isolated printers everywhere that can print anything, he envisages clusters of 3D printers at production sites turning out parts rather than full products. ‘These will probably engender their own supply chain,’ he adds.

And what of tomorrow’s air freight terminal? Eggert sees a role for self-driving vehicles and robots, but he does not expect facilities devoid of humans.

‘We won’t see a hands-free warehouse; air cargo is too complicated for that,’ he says. ‘Humans will continue to play a role in the warehouse, but they will be supported by technology.’

Just how it gets to the end customer is up for grabs.